Thoughts on Block NYT and how to understand information bubbles

Block NYT: An interesting experiment.

The filter bubble is a 21st century phenomena. It’s become common knowledge that algorithms have a powerful impact on our lives. And although there is debate about the extent of the problem, we know that in an effort to personalize our online experience, algorithms on social media give us information that conform to our beliefs and reinforce them. These ideas have been around since Eli Parsier’s bestselling book The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You. And over the last several years, the filter bubble has become an all too familiar concept. Many of us have heard the stories of people obsessing over conspiracy theories on youtube or falling down rabbit holes that result in crazy things like pizzagate.

Much has been said about filter bubbles, whether algorithms are to blame, whether governments should regulate misinformation, etc. But a recent movement got me thinking about filter bubbles in a different light. A group called Block NYT set up a site that lets users block 800 New York Times reporters from their Twitter accounts. Why would you want to block NYT? Well, the Block NYT website is littered with examples of how NYT has published misinformation over the years. And they aren’t the only ones that are critical of NYT. The Grey Lady Winked is an interesting read that illustrates how reporting from the NYT has altered public opinion, legitimized questionable decisions by the U.S. government, and changed the course of history. It’s a big claim. And it highlights how important the problem of misinformation is.

The point of this article isn’t to take sides with Block NYT or convince you to cancel your NYT subscription. Instead I’m more interested in the idea of the wholesale blocking of a well known news organization. It’s a unique experiment because it’s indicative of a group of people truly taking charge of their filter bubble. For better or worse, they’re removing a certain set of people, perspectives, and information from their social network. And that’s really interesting. We all live in filter bubbles of some sort. We all have a finite set of information we can consume. And although filter bubbles can magnify our biases, they can also help us to find signal in the noise. So what are costs and benefits to blocking the NYT, or any source of information for that matter? What kind of control do we have over our filter bubbles, what kind of control should we have?

A filter bubble is a type of information bubble. And we’ve had information bubbles forever.

Here’s the definition of filter bubble from Wikipedia:

”A filter bubble or ideological frame is a state of intellectual isolation that can result from personalized searches when a website algorithm selectively guesses what information a user would like to see based on information about the user, such as location, past click-behavior and search history”.

However, the definition for filter bubble, and the way we talk about them, leaves out the fact that we’ve been dealing with information bubbles since forever. It’s important to distinguish the term filter bubble from information bubble, and recognize that information bubbles are inevitable. An information bubble is the more general form of a filter bubble and is formed by the biases and beliefs in our offline social networks as well as our online ones. Like filter bubbles, information bubbles are created by our beliefs and biases. However an information bubble doesn’t necessarily depend on the internet or an algorithm, although it can. An information bubble is a phenomena that exists because we live in a world with a relatively infinite amount of information but a finite amount of time. It means that one way or another we need to have some means to choose the information we consume. Offline social networks play a huge part in the formation of our identity, our likes and our dislikes, and the kinds of information we consume. These can come from our family, our friends, the part of the country we were raised in. We’ve always had information bubbles that dictate our beliefs and biases. But the internet has exponentially increased the creation, distribution, and consumption of information. The abundance of information has given rise to algorithms that contribute to the formation of a specific kind of information bubble called the filter bubble.

It’s important for us to understand how information bubbles work, how they affect us, and how we can control them. This is because information has a huge impact on our lives. It forms our beliefs, dictates our behavior, give us our understanding of reality, and aligns us with our communities.

There are good bubbles and bad bubbles.

Information bubbles aren’t necessarily good or bad. The effect they have on our ability to process information determines their value.

Information bubbles can be good.

1.) In a world of abundant information information bubbles make it easier to find signal in the noise. The world has a relatively infinite amount of information. We cannot consume all of it. Bubbles help to filter information based on the information that we want.

2.) Information bubbles amplify the sources of information that we trust. Not all information is equal. Some sources of information are more useful than others. To that end, information bubbles, can be used as a way to identify sources of information that we can trust over others, simply because we’ve trusted them in the past.

3.) Information bubbles can lead to the formation of communities of people that share interest in a certain topic or align around a certain position. We find like minded people this way. And with the advent of social networks we can engage with them as well.

Information bubbles can be bad.

1.) Information bubbles can lead to selection bias. Selection bias is introduced when we pick individuals, groups, or data in a way that is not representative of the sample. Incomplete data results in an incomplete understanding of reality. And this is true of information that we get on the internet. As an example, consuming information from only one side of the political spectrum may hide important realities that the other side readily identifies.

2.) Information bubbles can be lead to confirmation bias. If we only consume information that conforms to our beliefs and reinforces them, then we tend to strongly hold the beliefs we already have even if they might not be true.

There are conscious and unconscious bubbles.

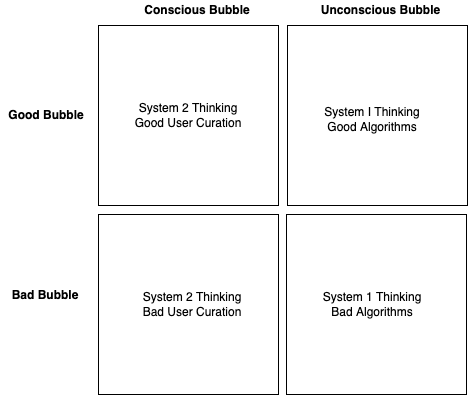

Another important distinction is conscious and unconscious information bubbles. This has to do with how aware we are of our information bubbles forming and existing. Daniel Kahneman has a great lens through which to think about this called System 1 and System 2 thinking. System 1 thinking is fast, instinctive, and emotional while System 2 is slow, deliberative, and logical. Often System 1 is unconscious and System 2 is conscious.

Unconscious bubbles are those that are created due to System 1 thinking. These information bubbles are not created with a high degree of awareness. What does this mean? It’s the type of bubbles that form as we’re scrolling mindlessly through our Twitter feed, our clicking at viral clickbait on our news feed. When we’re trapped in unconscious information bubbles we have a tendency to be more reactive. And the information that we find in these bubbles tend to appeal to our instinct, emotions, and ego. We’re less likely to think critically about what we’re consuming, we’re less less likely to evaluate whether the information is good or bad, and less likely to separate fact from opinion, and reporting from analysis. Entertainment tends to fall in the unconscious category.

On the other hand, conscious bubbles are created through System 2 thinking. Often we intentionally create them because we’re looking for information for a particular reason. We’re more likely to think critically think about information in these bubbles, and more likely to look for evidence and facts that support the arguments being made. We may tend to spend more time in our head, connecting this information to things we already know, and giving ourselves time and space to reflect on the ideas. Conscious bubbles are less likely to be purely entertainment, and are more likely to be proactive. It’s no surprise that information we consume to make us better at our jobs or to educate us at some skill tend to be in this bubble.

Classifying Information Bubbles.

The matrix above is a gross simplification but it’s a useful model for thinking about the different kinds of information bubbles. A few observations...

Observation #1: The move from a “good conscious” information bubble to a “good unconscious” bubble is the beginning of a slippery slope. Once we move from System 2 thinking to System 1 thinking, we run the risk of not being aware of whether an information bubble is good or bad. If a good algorithm turns bad, how are we supposed to know unless we’re aware of the algorithms effect on our information bubble? It’s possible that the algorithms that dictate our information on social networks have changed over time, and unless we’re aware of those changes and their effect on us and the people around us, it’s very difficult to change the status quo. Why would the algorithms change? Much can be said about this, but in short there are economic incentives for algorithms to extract value out of their users through advertising. The main point is that being conscious of our information bubble, its formation, and it’s effect on our knowledge is critically important to optimizing for good information bubbles. We may fall into an automatic pattern of consuming information from the same sources, or trust the same people for the news, but the minute that we stop critically evaluating the validity and quality of the information is the minute we run the risk of falling unconsciously into a bad information bubble.

Observation #2: “Bad unconscious” bubbles are the most dangerous kinds of bubbles. When people worry about filter bubbles on our social networks, they worry about “bad unconscious” bubbles. “Bad unconscious” bubbles are formed when we’re scrolling mindlessly on twitter, or when we read clickbait shared on our newsfeed. System 2 thinking is the solution. If we can become more conscious about our information consumption choices, more intentional about why we want to consume information, more goal oriented about what we want information for and how well the information is meeting our goals, then we can evaluate how well our current bubbles are working for us. Right now, our social networks aren’t incentivizing System 2 thinking, in fact, there may be economic incentives for algorithms to promote System 1 thinking. We need both individuals and platforms to promote System 2 thinking in order to optimize for the best information bubbles. It’ll be interesting to see if we can build technologies to do this in the future.

Observation #3: We should strive to create more “good conscious” bubbles. This means creating technologies and incentives that promote System 2 thinking. Social media algorithms aren’t the only ways in which we need to consume information. Indeed, technologies like RSS give users more control over their news feeds. And apps like Discord have become a popular way for communities to exchange information without an algorithm getting in the way. We should better understand what the pros and cons of a system where the user has more control over their bubble, and perhaps ways in which was can improve the design and implementation of technology to promote System 2 thinking.

Back to Block NYT.

So how does all of this effect how we think of Block NYT? Well in theory, it’s a great thing because it’s an example of System 2 thinking in action. The community identified a portion of their bubble that wasn’t working for them. And in this case it wasn’t working because they believed NYT lacked the truth and integrity that they expect from a news organization. Perhaps more people should think about blocking, or at least curating their feeds. Twitter Lists are a great way to have more control of your information bubble on Twitter.

At the same time, we we should hope that each member of the Block NYT is using System 2 thinking to make their decision. Changing our information bubbles can radically alter our understanding of the world, and if we’re blocking a source just because someone else is, or because it sounds like the cool thing to do, then all we’re doing is reverting to System 1 thinking again. The other issue is that there can actually be value in understanding an information source, and the wider bubble it lives in, even if you don’t trust it. To the extent that NYT is an unreliable news source, understanding what information it publishes can be an opportunity for other news organizations to publish higher quality information that people can trust. It can be useful to learn about what kinds of information NYT’s audience is consuming, and it can be valuable to publish information that identifies and fights misinformation publicly. This isn’t everyone’s job but it’s important to keep in mind.

Ultimately, we live in a world with relatively infinite information but a finite amount of time to consume it. Information bubbles are inevitable. And they have costs and benefits. System 2 thinking is key to understanding our information bubbles and how to manage them so that we can make the best use of information that is available to us. We should continue to promote this type of thinking as individuals, and I’m excited to see what technologies can be built that can promote this type of thinking as well.